Maximum Confusion, Minimum Choice: How “May Contain” Labels Fail People With Food Allergies

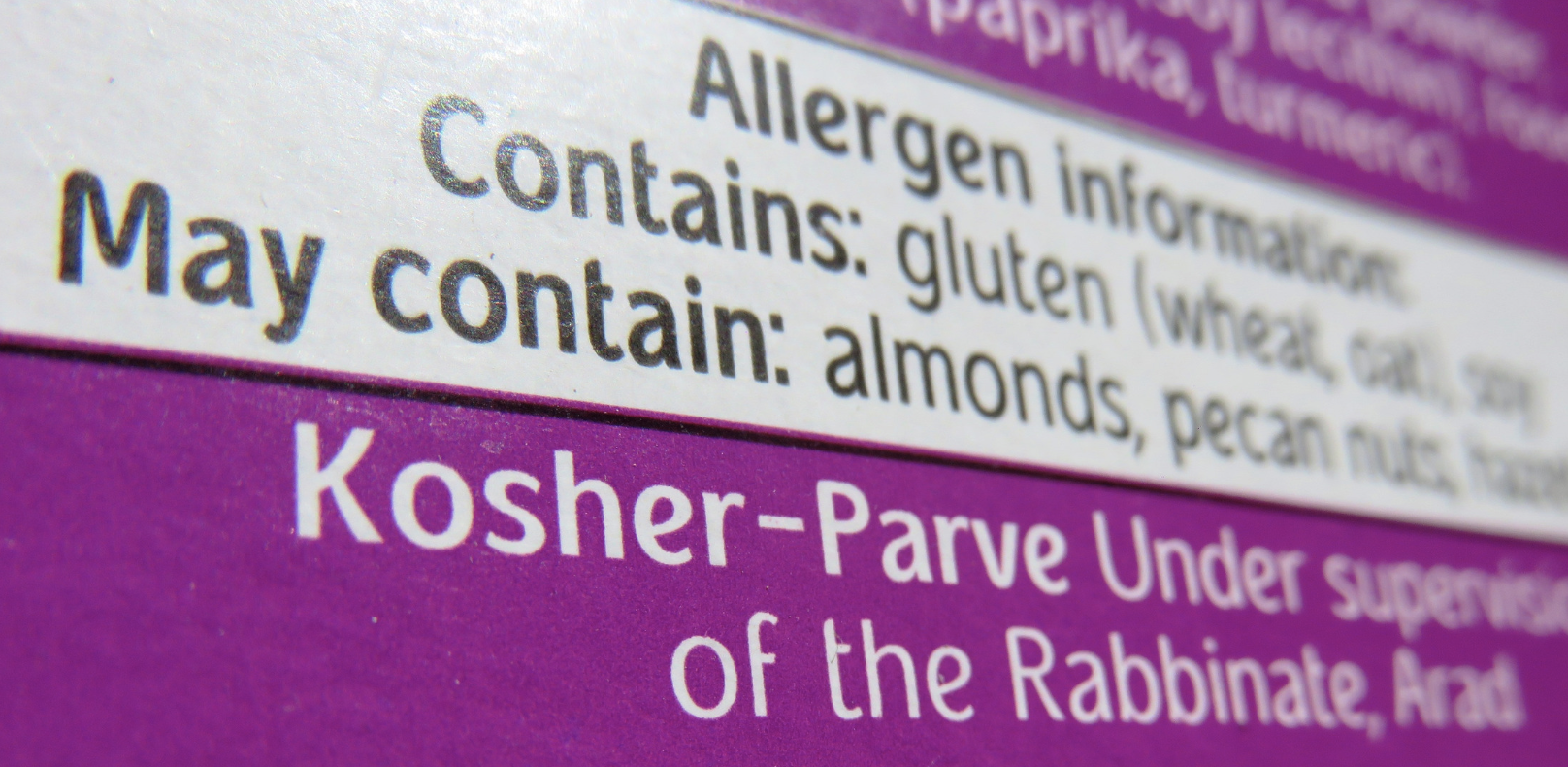

For people living with food allergies, food labels are not just information, they are a vital safety tool. Yet one of the most common labels on supermarket shelves, “may contain”, is also one of the most confusing.

Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL), better known as “may contain”, was designed to warn consumers about genuine cross‑contamination risks. But in practice, it has become inconsistent, overused and difficult to trust. For families managing food allergies every day, this often results in anxiety, reduced choice and avoidance of foods that may actually be safe.

Now, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) is considering a major change that could bring long‑awaited clarity to “may contain” allergen labelling. Here’s what it means and why it matters.

In brief: what you need to know about “may contain” labels

“May contain” allergen labels are currently unregulated and inconsistently used.

Overuse has led to confusion and a lack of trust among people with food allergies.

The FSA is exploring a science‑based threshold system known as ED05.

This could reduce unnecessary warnings and increase food choice - if properly regulated.

Clear communication and education will be essential to keep people safe.

What are “may contain” allergen labels?

“May contain” labels fall under Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL). They are intended to warn consumers when there is a risk that a food may contain trace amounts of an allergen due to cross‑contamination during production.

In theory, PAL helps people with food allergies make safer choices. In reality, there is currently no legal frameworkgoverning when or how these labels should be used.

This means manufacturers can apply a “may contain” warning regardless of the actual level of allergen present or even when no allergen is detected at all.

Why are “may contain” labels a problem for people with food allergies?

For years, people with food allergies and their families have had to navigate a labelling landscape that is inconsistent and confusing. Without regulation or oversight, “may contain” labelling has become the Wild West of food labelling.

Many in the food allergy community feel that some manufacturers rely on PAL as a form of protection from legal risk, rather than taking steps to properly assess and manage allergen risks.

As a result:

People lose confidence in food labels.

Families avoid entire categories of food.

Choice becomes increasingly limited.

Anxiety becomes part of everyday food decisions.

What families are telling Natasha’s Foundation

Feedback shared with Natasha’s Foundation highlights deep frustration with the current system. Common concerns include:

Unclear definitions of what “may contain” actually means.

Inconsistent use of PAL across brands and businesses.

Over‑reliance on warnings for convenience or legal protection.

Vague labels such as “may contain nuts” that fail to distinguish between peanuts and tree nuts, which are separate allergens.

In short, the current approach offers maximum confusion and minimum choice for cautious food‑allergic individuals.

What is ED05 and why is the FSA considering it?

In December, the Food Standards Agency met to consider a new approach to “may contain” allergen labelling based on evidence‑based allergen thresholds.

The FSA board unanimously supported aligning the UK with international work led by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, which aims to introduce a consistent global approach to PAL.

Central to this proposal is ED05.

ED05 represents the amount of an allergen that could cause a reaction in around 5% of people with that allergy. Based on current scientific evidence, reactions at this level are expected to be mild to moderate, according to the FSA.

Under this model, only foods that meet or exceed the ED05 threshold would be allowed to carry a “may contain” label.

Could evidence‑based allergen thresholds improve safety?

If implemented correctly, a threshold‑based system could be transformative.

It would replace guesswork and blanket warnings with a science‑led approach, helping to ensure that “may contain” labels are meaningful and trustworthy.

Similar systems are already gaining traction internationally, including in Australia and the Netherlands, where structured allergen risk assessment models are in place.

As a Foundation advocating for greater safety for people with food allergies, we welcome the FSA’s work to explore this approach.

However, ED05 alone is not enough.

What must happen for this system to work

A threshold system will only be credible if it is supported by:

Clear regulation, not voluntary uptake.

Consistent enforcement across the food industry.

Transparent and accessible communication for consumers.

Ongoing monitoring and review.

Changing how “may contain” labelling works is pointless if people with food allergies are not aware of what has changed or how to interpret it.

Global bodies, including the World Health Organisation’s Codex Commission, emphasise that threshold‑based labelling must go hand‑in‑hand with comprehensive public education.

Consumers, clinicians and retailers all need to understand what ED05 means in everyday terms including that:

A product without a PAL label is considered safe for most people with that allergy.

A product with a PAL label carries a higher, but clearly defined, level of risk.

Improving information and rebuilding trust

Clear communication must be matched with better access to information.

Practical tools such as scannable barcodes linking to detailed ingredient and manufacturing information, as recommended by Allergy UK - could help build trust, particularly for those who may react below ED05.

Education is equally important. People with food allergies need support to understand thresholds, personal risk levels and ongoing management. No system can ever remove risk entirely, but clarity empowers safer decision‑making.

Collaboration is essential

For ED05 to genuinely improve safety and choice, collaboration will be key.

Supermarkets, manufacturers and the hospitality industry must work together to adopt best practice, drawing on effective international models such as Australia’s VITAL scheme, a standardised allergen risk assessment process.

This must include practical support for businesses of all sizes, ensuring that new requirements improve safety without creating unintended risks.

A lifeline, not a luxury

An overhaul of the “may contain” system is essential and long overdue.

Evidence‑based thresholds for precautionary allergen labelling could give people with food allergies and their families the chance to make genuinely informed choices and may even increase choice by reducing unnecessary warnings.

But significant hurdles remain. Without strong regulation, clear communication and long‑term education, reform will not deliver the change that millions of people in the UK living with food allergies desperately need.

The Natasha Allergy Research Foundation will continue to champion the voices of people with food allergies and their families throughout this process.

Working alongside Allergy UK, Anaphylaxis UK, policymakers, scientists, food businesses and our community, we will advocate for a system that is scientifically robust and genuinely meets the needs of those it is designed to protect.

For people living with food allergies, clear and trustworthy labelling is not a luxury - it is a lifeline.

Written by Glen Watson, Policy and Public Affairs Manager for Natasha’s Foundation